Pre-Race

On September 25th I rode my first event in Texas — the Texas Time Trials. They are hosted by Dan Discroll, who is also the RBA (organizer) of a local randonneuring group. They are put on in the community of Glen Rose, some 90-minutes SW of Dallas.

I flew in the previous day so I could get my bike assembled and make sure everything was working. This was my first experience in shipping or flying with a bike, so I was a bit apprehensive. I shipped it ahead using the service Bike Flights (via UPS Ground). The cost was about the same as flying with on Southwest Airlines — it was waiting for me at the motel, so I didn’t have to hassle with it in the airport and rental car.

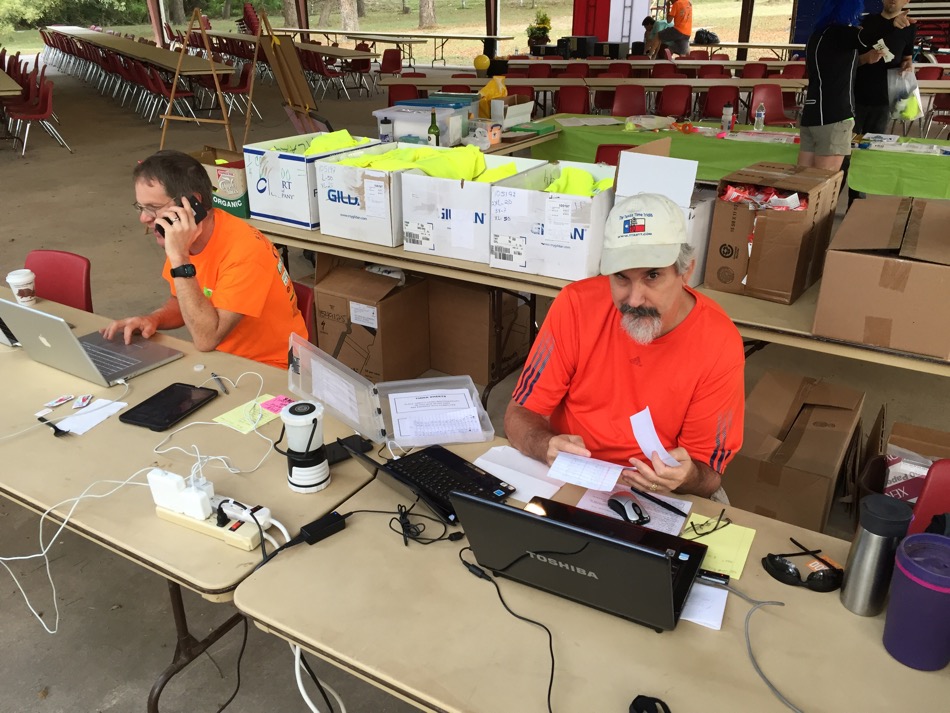

This non-drafting 24-hour “Iron Butt” race started at 5:00 p.m. on Friday. Other events started earlier or later, depending on the distance. Upon my arrival I received a warm greeting from Dan and his co-organizer, Pam Wright. I also meet volunteer Gary Gottlieb, who is a legendary distance cyclist and local randonneur.

During the day on Friday, I just chilled in the shade of the pavilion and pre-loaded electrolytes and fluids. The forecasted high was in the mid to upper 80s. Perfect weather. Since I was flying in, I prearranged to share my “pit” with a friend I met at the Texas Hotter N’ Hell show, Larry Eads. He provided me with a cooler and I was able to share his tent.

I had looked at the route ahead of time online, and unlike the other 24-hour race which I did the prior season, this one had a lot more climbing. I had a 12-30 cassette on my 10-speed carbon wheel, but the cranks were the typical time trial configuration, which is 53-39. I was a little apprehensive that this gearing may not be low enough, especially later in the race, as I tire and my strength drops. The loop was 26.4 miles with about 1200 feet of climbing.

Night Riding

The race started on time and I carried two water bottles on my bike. One on the bottle cage and a 2nd on a jury-rigged insulated pouch mounted underneath my aerobars. This necessitated stopping and pulling it out to switch as I couldn’t quite reach around far enough while clipped in. I started out with Hammer Perpeteum in my main bottle and fig newtons in my eoGEAR Century Deluxe top tube bag. My stomach was a little queasy for the first hour or two, but it later settled down. I did not have a crew person, so the idea was to stop at the “pit” every few hours, or as needed, to refill my bottles, eat solid foods and top off my top tube bag with more nutrition.

I managed to get in four laps before I ran out of fluids, so finally, after knocking out a little over a 100 miles, I stopped at the pit and topped off everything. In cooler temperatures, I find I can go a quite a distance with minimal fluids, as long as I have sufficient nutrition. The night was so comfortably warm, so that I only needed to add arm warmers. I had a wind vest stashed in my seat bag, but ended up not needing it. What a difference to riding in Utah, where the temps drop down do 40 or 50F at night in the summer or early fall. The key to night riding is to keep moving and not stop for very long, otherwise you will chill and want to put on more clothing, that may cause overheating later on. I did have to be mindful of my battery life of my front “white” light and also switch out batteries during the night. As it turns out, with my Cyglolite 740Xtra, one large and one small battery were enough to get me through the night. Since I was doing the same loop over and over again, I was able to ride with my light on the lowest setting, since I became familiar with each of the turns and stops. At one point, in the middle of the night, I did see out ahead, a “thing” cross the road — it appeared to be an armadillo, but I could not be sure. I would hate to have an encounter with one those with my skinny 25mm-wide tires!

This route had many short rollers (up to 6%) and consequently, I found myself out of the saddle on the climbs and in the aerobars on the flats and downhills, as I tried to build up speed for each upcoming hill. Consequently, I had no “Shermer’s Neck” problems because I was moving around enough on the bike and not constantly in the aero position.

Finally, Daylight

Sunrise finally came and at the first opportunity, I dumped off my lighting gear to save weight. I am rejuvenated by the sun and my pace seemed to pick up a little. Later in the day, it did get pretty hot, but I used insulated bottles and filled them with lots of ice. I don’t mind temperatures in the mid to upper 80s, as long as I can keep cold fluids going down. With the heat, I ended up stopping nearly every 26-mile lap to refill both of my bottles. At one point, I passed another cyclist who was walking his bike on a rather flat section and I asked “are you OK, need anything?” His response was “yeah, I just need a new back!”

As we rode into the city of Glen Rose, the organizers had arranged for a police officer to be at the main downtown light and wave us through, holding up traffic. That was nice as it was at the bottom of a gradual hill. I had no flats or mechanicals, so I didn’t need the roving support vehicles that cruised the route 24/7.

The Results

I just kept on doing laps and ended up rolling into the finish line with 344 miles and about 20 minutes left on the clock. This race offers no short loop option, so if I wanted to get more mileage, I would have to complete another complete lap, which was taking over 90 minutes each and they would pro-rate my mileage for the 20-minutes left. As it turns out, I was the only 60-year old in my category, so I had nobody to “beat,” and I decided to call it quits. That provided me with a 5th place overall finish, out of 18 solo guys (of all ages). 1st through 4 get a spot on the podium.

Afterwards I headed to my motel (across the street) and showered. At 7:00 p.m. was a great banquet and awards ceremony, after which I promptly proceeded to my room to catch up on some badly needed sleep.

Many thanks to Dan, Pam and their many volunteers for sponsoring such an epic event. This is the 14th year for this event. And I extend my appreciation to Larry Eads for taking me under his arm and sharing pit space and his hospitality.

My Strava upload.

Followup

After arriving home, I wrote an e-mail to Dan with the following feedback and impressions of this well-organized event. Most of it is below:

- No rumble strips on the route (they are MUCH worse than chip seal, which we also have a lot of in Utah)

- No tight “dangerous” turns on the downhills. I could bomb them all, as they had decent run outs.

- Blinky lights at T intersections was most helpful

- Mileage markers all along the route were appreciated

- Easy, common-sense reflective gear rules (not as rigid as 24-hour World’s in Boreggo Springs, CA)

- End of season timing, which works for me, since I don’t usually start doing long (300K or longer) rides until May

- Friday-Saturday riding with no cycling on Sunday (that is due to my Christian religious-convictions)

Con:

- This course as a fair amount of climbing for a time trial event. My GPS showed 1,131 feet per lap. I wonder if you had a flatter course, that you might attract more triathletes, which would use this for training purposes (although in September, most are done for the season).

- No small “end of day” loop. If you roll in with time left on the clock they allow you to finish one more lap and then pro-rate your mileage accordingly. I rolled in with 20 minutes left on the clock. Mentally, I just couldn’t deal with doing another full enchilada lap (90+ minutes)…and get such a small portion credited to me. Is doing an out-and-back with a turnaround before the Nemo climb, not feasible? With a couple of volunteers stationed there, verifying completion of laps? Too many riders to keep track of? I understand that Bessie’s Creek 24-hour race, also in Texas, has some sort of honor system for doing partial laps.